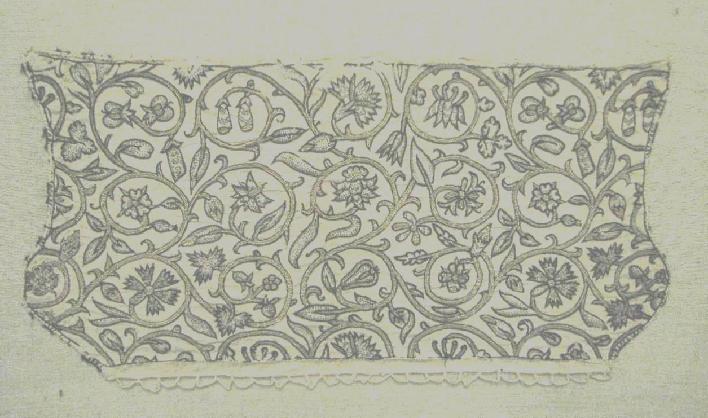

This is my copy of coif T.28-1975 in the Victoria & Albert Museum, London. Like many surviving items of this kind, it can only be dated roughly to about 1600, but embroidered coifs start showing up in portraits in the last quarter of the 16th century. Judging by the shape of the coif and the design of the embroidery, it could date anywhere from 1580-1610.

|

|

| V&A Museum, London |

|

This is the original coif, as it sits on display in the museum. When put together, it would be shaped like the reproduction at the top of the page. It is embroidered with black silk and gilt thread on 104tpi (threads per inch) linen. The original uses plaited braid, ladder braid, chain, stem, hem and speckle stitches.

Opinion is divided on whether many of these surviving coifs were made by professionals or amateurs1. However, I can say from direct experience that this particular coif is perfectly manageable for anyone with reasonable embroidery skills. Certainly by 1600, many embroidery patterns and books were available to women who wanted to do their own embroidery, and artists/professional embroiderers offered design and drawing services2 for women who needed the design drawn out for them.

|

|

| V&A Museum, London |

|

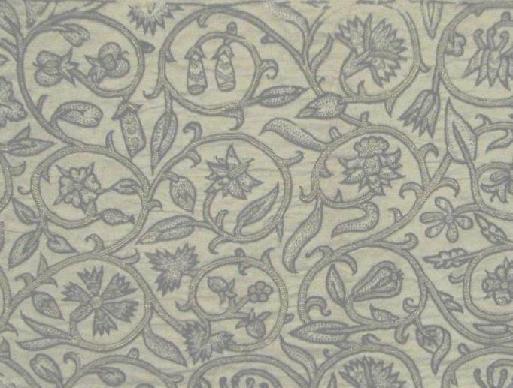

The embroidery design repeats every three vines up and down, and every four vines sideways. It is possible that this was copied from a pattern intended for a larger piece such as a cushion, as the repeating effect is lost on a piece this small (though the design is still extremely attractive). Even at this size, however, it fits well with Elizabethan decorative sensibilities - it fills the available space without any large blank areas. In fact, the edges of the design are a little bit crammed in to make sure the space is properly filled; to the Elizabethan eye, overcrowded is better than too sparse.

The vines are outlined in black silk, then filled in with plaited braid stitch in gilt. The flowers and leaves are quite randomly decorated (which lends support to the argument that this was produced by an amateur - a professional might make the design more symmetrical), and there is no real pattern or order to the gilt thread stitching. The speckle stitch is quite large - larger than my reproduction speckle - and is used to create patterns as well as shading.

|

The original measures roughly 9" high by 18" wide at its widest point, with the main embroidery design worked to 1/4" from the edge of the coif. The base edge is left plain, and the rest of the edges are worked with a hem stitch that is now mostly missing. Instead of the drawstring casing that is sewn on almost all of other extant coifs, T.28-1975 has 27 buttonhole-stitch loops that are roughly 1/2" square and made of white linen thread. It is possible that this was done to make the coif fit a slightly larger head, but it's just as possible that the maker thought the loops looked nice, or that she didn't leave enough fabric to turn under for a casing.

|

|

| V&A Museum, London |

|

Who wore embroidered coifs? The answer, honestly, is any woman who could afford to make or buy one. 16th century England, especially London, was mad for gorgeous decoration, and an embroidered coif was a small enough item that both material and time-wise, it was within the capabilities and budget of many women. A polychrome silk, gilt, and spangled coif would have been too expensive for most women (and more likely to be made by a professional embroiderer), but a monochrome coif like the repeated motif one pictured right would be a little bit cheaper to make, especially if no gilt thread was used.

While there are no surviving coifs embroidered in anything but silk, it is quite probable that women would also embroider designs in wool and linen threads. Only the best and most precious things get saved from age to age (most 16th century garments were remade and reworn until they fell apart and the fibres were recycled); a wool or linen coif would probably not be considered valuable enough to keep.

|

|

A detailed examination of extant coifs shows that once embroidered, the coif is hemmed with very small stitches, then possibly sewn to a linen lining. I feel that for my coifs, the lining is neccessary to protect the material from hair oils and dirt; once embroidered, the delicate nature of the dyed silks means that washing is almost impossible without damaging the embroidery. A lining can be replaced once it becomes too soiled, and since cleaning methods for very delicate items are complicated and possibly damaging3, it makes a certain amount of sense to protect against extra dirt. My theory for this is based in part on a coif in the V&A which has a wear spot that shows a linen fabric underneath of the exact same thread count and colour as the coif, though it must be pointed out that the coif is permanently mounted under glass, so a proper examination is impossible.

Two possible stitches are used for hemming: A straight running stitch, or a very small whip stitch. An examination with a magnifying glass of T.28-1975 showed a very slight and persistent angle on the hemming stitch that is consistent with a whip stitch that only picks up one or two threads on the outside of the hem. It is also possible that unlined coifs in the collection could have a lining attached which was attached at the edge of the hemmed coif, whereby no stitching would show at all, or could be confused with the stitching used to hold on a lace edging.4

|

When I decided to make my copy of T.28-1975, I used a detailed sketch I made of the coif on a previous visit to the V&A. Making a sketch rather than simply taking a picture and working from that forced me to really see the design and stitches, and I made notes as I drew.

I enlarged the sketch to the proportions of the original (on a photocopier - a trial and error process that involved a tape measure and many notes), and transferred the design pattern to the linen (I used 64tpi linen) by taping the full size paper pattern to my balcony window, then taping the linen taut over it, thereby creating a kind of light table that enabled me to see the design easily through the fabric.

NOTE: When you use this method pf pattern transfer, make sure you don't stretch the fabric on the bias, or the pattern will be distorted.

I drew out the pattern using a Micron brand size 001 archival pen (black). In the 16th century, they would have used a fine quill pen and carbon black ink, the remnants of which are sometimes visible on extant pieces. When a 16th century embroiderer drew out a pattern, the linen was probably ironed and starched, which would prevent ink bleed, and the finer the linen, the smoother the ink line will be. My linen was little more than half the thread count of the 16th century original, and I felt that even ironing and starching the fabric wouldn't make the line smooth enough or stop the period ink from bleeding, so I went with a modern waterproof archival ink pen. This had the added advantage of not smudging or transferring to other parts of the fabric if my hands got damp or the embroidery got wet.

Some day I'll be brave enough to try the period method on something more than a sample, but not yet.

|

|

| picture copyright V. Dye, 2006 |

|

I made some changes from the original. I used double-running stitch, speckle stitch, and hem stitch instead of the original stitches because I'm not as accomplished an embroiderer as my 16th century counterpart, and I'm not comfortable working with gold thread. I added spangles - flat sequins made from hammered wire - for a little sparkle, speckled more of the design, and created a channel for the drawstring instead of the loops (not because I can't do those, but because I thought the channel looked tidier and would gather better).

|

I lined the coif with a slightly coarser linen - hemming both lining and coif before stitching them together means that it will be easier to replace the lining if needed, but I will still have to unpick the hem stitch as I embroidered that part after lining (the original appears to do the same thing).

Once that was done, my coif was ready for final construction. I measured the length of the top seam once the coif was folded in half, then stitched together two thirds of that length. The last third I gathered into small pleats and pleated (I used cartridge pleats) to the end of the seamed two-thirds.

|

The coif is small; an argument can be made that it was intended for a child, but I found that my reproduction sat perfectly on my head so that the front part of my hair could be curled into the fashionable style of the period. There are portraits that show rich women with their hair fashionably styled and a suggestion of a coif in the back. I think that the coif may be of this nature, not a child's, but that is only based on my experience wearing the coif, which stays perfectly on my head without slipping when my hair is styled in a period manner.

The reproduction took roughly 200 hours (possibly more; I didn't track my time) over a period of about 6-8 months.

|

Notes:

1. Elizabethan Embroidery, George Wingfield Digby, 1963. Chapter 2 has a good discussion of domestic vs. professional embroidery and embroiderers.

2. Ibid. Mary Queen of Scots, while imprisoned at Lochleven Castle, petitioned for "an imbroiderer to draw forth such works as [she] would be occupied about". The implication is that they were needed as much for drawing out the design as embroidering it. Professional embroiderers were all men - it was a guild-controlled activity in London, and even outside of London, womenwould not have been allowed to set up an independent shop, no matter how skilled they were.

3. A conversation with Susan North, curator of 17th and 18th century fashion, V&A Museum, London revealed that fine embroideries were not washed - if they were attached to some other garment, they'd be unpicked if possible (for things such as skirt guards), or dry-cleaned with powder to soak up oils. Items soiled beyond repair were either recycled into something else (a couple of the coifs in the V&A appear to have been made from cut-down embroidered cushions), or sold and worn by someone lower down the social scale until the item fell apart. My thanks to her for the fascinating information.

4. V&A coif T.12-1948 - the coif is under glass, but enough fabric shows through the hole that a thread count was possible. Both the coif and the possible lining ae 72 threads per inch, and the same yellowed colour. All the thread stitching showing on the edges is the same , and I feel that it would be extremely difficult for conservational lining to be matched to the original fabric and sewing technique so exactly. However, it is important to note (because of possible misunderstandings) that this theory is my own, and is not widely accepted. Linings protect the work and can be easily replaced, so I feel it is important not to discount them entirely, since a large number of other embroidered pieces (nightcaps, jackets) from the era are lined, as well as the majority of unlined pieces, since linings also create structure and support for the highly architectural fashions of the day.

|

|